When World War II ended in 1945, there was an exceptionally brief period of time when America had unchecked power on the global stage. The Americans were the only ones with “the bomb,” after all. After the Soviet Union detonated its first bomb in August 1949, the Cold War between the two powers picked up substantially.

For the administration of Harry S. Truman, the strategy to win the Cold War became containment; the key to victory was to stop the spread of communism. This lead to the conflicts in Korea from 1950 to 1953, and the gradual escalation and the eventual scorched-earth strategy in Vietnam.

This idea of containment was not only promoted in the US foreign policy but also extended domestically, too. The idea of “anti-communism” permeated all aspects of American life from a rise in consumerism to infrastructure upgrades like the Interstate Highway System to politics and even to entertainment. Hollywood especially was a hotbed for anti-communist witchhunts and blacklists. In order to stay off the blacklist, many in Hollywood blatantly promoted sanitized, and often exclusively white ideas of the American life. Too often, these films promoted heterosexual relationships, cut most sexual references from films, and emphasized marriage and the nuclear family.

This is particularly true about 1950’s All About Eve and that film’s aggressive attacks on communism and homosexuality. This week’s film, An American in Paris from 1951, continues that trend, but in a different manner. Rather than being a dark film that literally portrays communists as evil, An American in Paris instead relies on familiar tropes of love and marriage, in addition to providing “wholesome” entertainment.

The movie, starring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron, was directed by Vicente Minelli is an odd love story between a starving artist and a lowly perfume store clerk and their search for each other. The film, which is based on music by George Gershwin with lyrics by his brother Ira, is both slow-moving and fast-paced, entertaining and boring, timeless and aged. While the musical does entertain at the time when considered as a whole, it fails to stand the test of time.

Also, I know this week was supposed to be Green Book. I had trouble getting it from the library in time. So I’ll cover that in my next blog.

Now, for the rest of the movie.

Plot/Writing

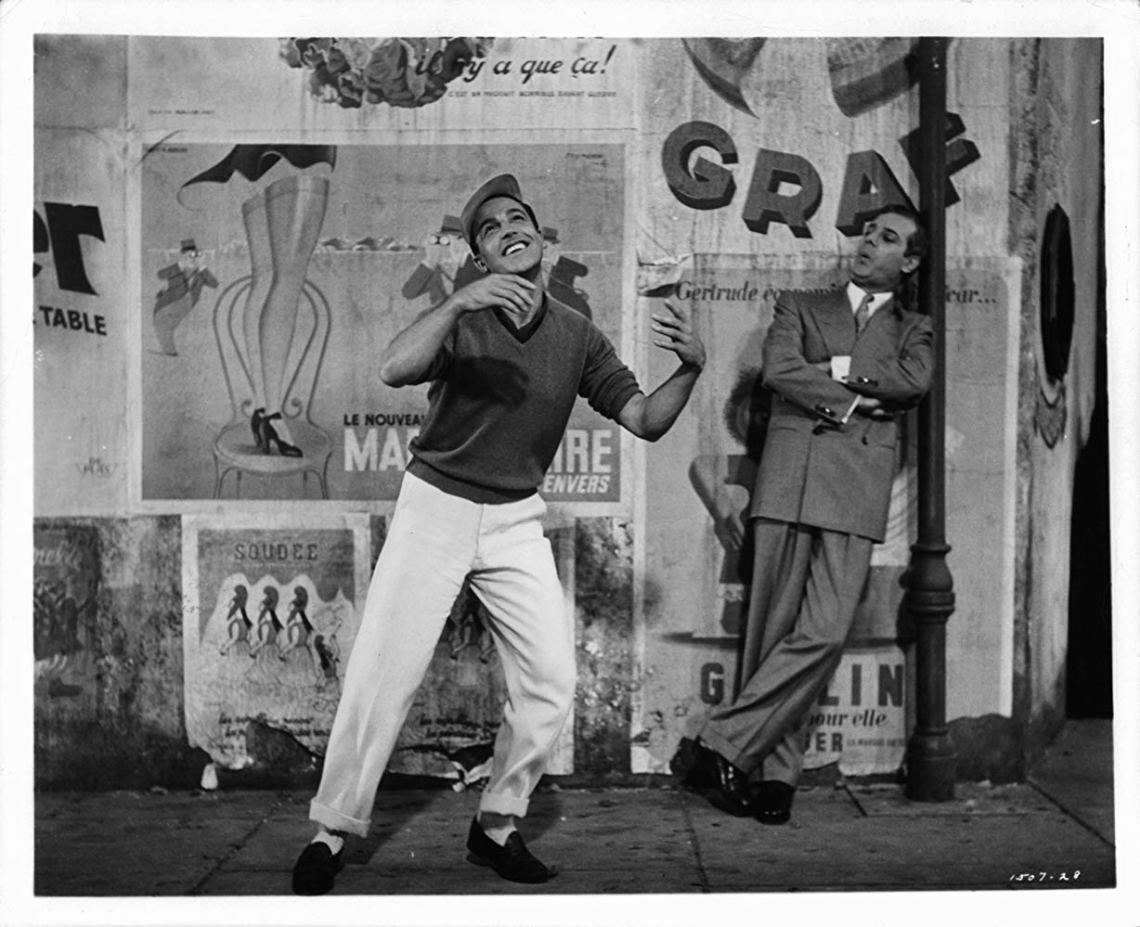

Gene Kelly stars as Jerry Mulligan, a down-on-his-luck artist trying to make his own way in Paris. As a veteran of the war, Jerry chose to stay in the city to hone his artistic talent. While there, he runs into another American, pianist Adam Cook (Oscar Levant) and the two become fast friends dying for inspiration in their respective arts. Jerry’s work gets noticed by the lonely (and somewhat aggressive) heiress Milo Roberts (Nina Foch) who agrees to sponsor his work and put on an exhibition for him. Along the way, he meets and falls in love with Lise (Leslie Caron) who is already in love with Henri (Georges Guetary), another person close to Jerry and Adam.

The rest of the film sees Jerry juggle his affection for Lise and the needs of Milo, her advances, and his art career. Eventually, the truth comes out that Lise and Henri are engaged and they will be running off to America for their honeymoon.

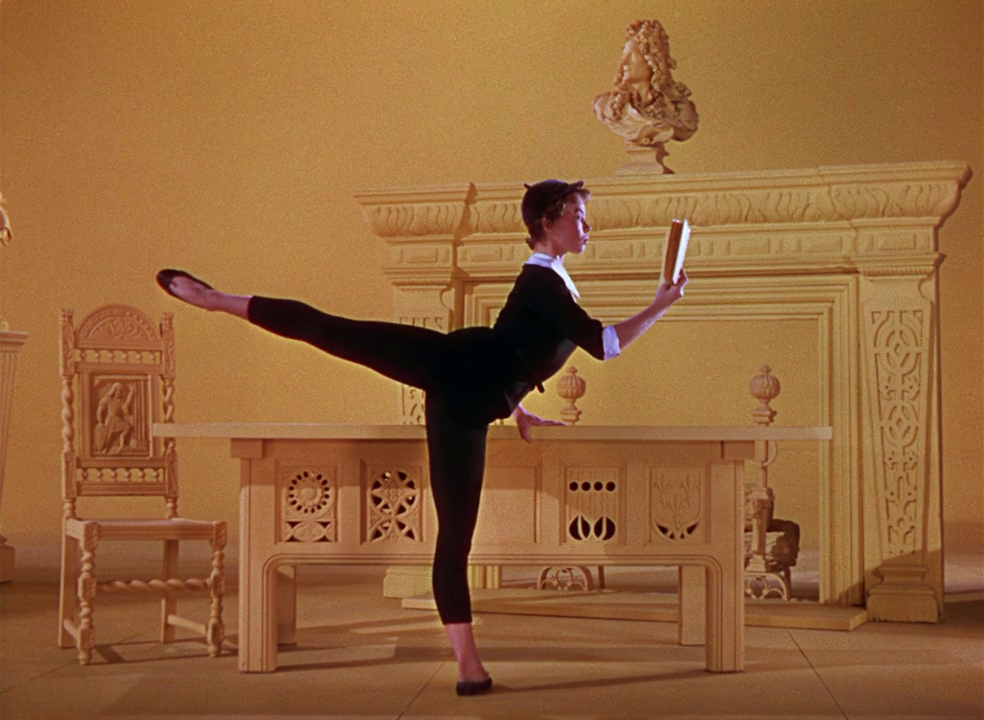

The film concludes with an incredible 18-minute ballet piece choreographed by Gene Kelly, that summarizes the relationship between Jerry and Lise before Lise returns to Jerry. Then it’s happily ever after.

From a structural perspective, the movie’s plot really moves at two speeds. The first half of the 113-minute film moves at a very slow pace, relying mostly on exposition. The initial 60 minutes or so lay down the themes of love and marriage, sure, but also does the most to establish the characters themselves. This includes their hopes, dreams, and fears.

The second half of the film ticks on at an increased pace and is full of nuance and real human emotion that escapes the overly generalized view of American life.

On the writing side, the film features not only witty dialogue that we’ve seen in earlier films but also a not-insignificant portion of the dialogue is in French. It helps to sell the film, in my opinion. After all, any ex-pat will surely pick up the local language.

Alan Jay Lerner wrote the screenplay for An American in Paris and he earned the Oscar for it at the 24th Academy Awards. 1. 1.

Sound

For all the versions of life that An American in Paris wants to portray, the film does do many things well. One of them is the movie’s music. Since it’s a musical, I’ll hold the film to a higher standard.

Getting the Oscar for the film’s scoring was Johnny Green and Saul Chaplin, but the inspiration for the music came from George Gershwin’s 1928 piece “An American in Paris.” From top to bottom, the film’s score is lively and catchy and each of the songs features terrific lyrics. Clearly, the performances were intended to be as grandiose as anything seen up to that point.

Two songs stick out to me in particular, “‘S Wonderful,” and “I’ll Build a Stairway To Paradise.” Both of these songs are massive in scope and have that “ear-worm” trait.

But the piece that steals the show has got to be the climactic ballet number at the end of the film. I’ll write more about this below, but the scoring and choreography are unlike anything I’ve seen in a movie. 1.

Set Design

An American in Paris took home two Academy Awards in this category: Best Costume Design and Best Set Decoration. On the costuming side, Orry-Kelly designed the clothing worn on set. Given the film’s Technicolor shooting, Orry-Kelly took advantage of bright and brilliant fabrics to lend a colorful and optimistic tone to the film. Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron pop off the screen at every chance, and this is especially true during the film’s ballet sequence at the end of the movie.

Complimenting the costuming was the set design, designed by Preston Ames and Edwin B. Willis. In 1951, movies were still shot on studio backlots in California, and this one is no exception. To give the impression of Paris at the time, Ames and Willis supplied beautiful, hand-painted backdrops. Even though the sets of Paris are clearly fake, I appreciated their beauty, and how they helped to establish An American in Paris as a stage musical that happens to be in front of a movie camera. 1.

Cinematography

Alfred Gilks was the director of photography for An American in Paris and he won Best Cinematography for the job.

The most evident touch that Gilks puts on the film is his use of cameras on dollies and cranes. I, for one, love a camera that moves with the action, particularly in the timeless way in films of yesteryear. Movement can accomplish so many different emotions without the viewer even realizing it. In An American in Paris, the whole emotional spectrum is set off by the movements of the lense.

This is particularly true in, yet again, the massive ballet sequence at the end of the film. Not only is Gene Kelly working every muscle in his body, but a large number of extras on the set means that the scene is constantly in chaos. Gilks does a brilliant job of capturing the chaos for the viewer. If the film was shot using other means, then it wouldn’t have been nearly as dynamic. 1.

Acting

Taking center stage in An American in Paris is Gene Kelly. This film was the rare movie to win Best Picture with no acting nominations. For me, I struggle with his portrayal of Jerry Mulligan.

On the one hand, Kelly radiates optimism. For being a down on his luck artist, Mulligan is surprisingly happy. But this isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I suppose he’s allowed to be happy, and that just makes him much more likable. He plays ball with children on the streets, is nice to all his friends, and is humbled by success.

But Kelly is also very hard to pin down. Sure, I wanted to like Mulligan, but I just couldn’t. At the end of the day, Jerry Mulligan is a man who tries too hard to make a woman like him, even after she clearly doesn’t. He’s a homewrecker, interrupting an engagement, and rejects recognition when it finally meets him, choosing instead to pursue love over his art. He moved to Paris after the war to be an artist. Then he shies away from the recognition of the art gives him? No, thank you. He was not as well-rounded, thought-out, or as interesting as I would have preferred him to be. 0.

Directing

Vicente Minnelli won the first of his two Best Picture Oscars with An American in Paris. He was nominated for Best Director for this film at the 24th Academy Awards.

From the beginning of the film, Minnelli exhibits a unique storytelling style that, frankly, I loved. The film begins with Jerry Mulligan narrating his life up to the point that we catch him in his tiny studio apartment snoozing on a bed that literally hangs from the ceiling. Not only that, the train of thought shifts from Jerry to Adam and then finally to Henri as they go about their daily lives. This isn’t used in the film again, but I don’t think it needed to be.

Second, Minnelli often breaks from the narrative to jump into a character’s mind, showing their deepest desires. The most interesting of these, outside the ballet sequence at the end of the film, is Adam’s dream of being a concert pianist. His dream is both fantastical and abstract. He is the pianist, the orchestra, the conductor, and every member of the audience. I’ve struggled with what this actually means, but my first instinct is to believe that the sequence illustrates his idea that he’s really the only one who appreciates his work and the only one that can make his dream into a reality.

For all the good that these two examples give, there is plenty to be concerned about in the film too. American in literally in the film’s title and the movie seems to always emphasize the Americans that are in Paris. In fact, they’re specifically pointed out during the film as being walkers on the street or members in the audience. This, to me, is telling of one of my favorite topics: American exceptionalism, or the belief, held by Americans, that Americans are special and unique on the world stage.

This idea only furthers the feeling that America and the American way of life are preferable to alternatives, particularly communism. The implications of this idea are obvious to me: it only reinforces the notion that American capitalism should not be questioned. The French, in particular, love the Americans in the film. Thus, the rest of the world does, too.

My other beef with Minnelli’s film is the ballet scene itself. I’ve raved about the scene previously in this review and it deserves all the praise it gets. The sequence is truly a masterpiece. But it also deserves some criticism, too.

Since the recent Christmas season, the first thing that came to mind when I watched this scene was “The Nutcracker.” I’ve seen the ballet but being a country bumpkin from the plains of Kansas, it remains the only ballet I’ve seen. To say I was disappointed in “The Nutcracker” would be an understatement. The first half of the ballet had actual substance, the second half was just interpretive dance. It was beautiful, don’t get me wrong here, but it seemed odd to only put any kind of story in the first half of the show. However, this may be my general inexperience with ballet, but I didn’t care for it.

The same is true for the scene at the end of the film. As well done as it was, it felt more like a convenient plot device to eat up 17 minutes of the film before Lise actually returns to Jerry. It does nothing to advance the plot, but rather only as a recap of the story up to this point, only with interpretive dance.

The score to give this category kept me up at night this week. I wavered between forgiving these sins and not forgiving them. When considering the movie as a whole, it reminded me somewhat of The English Patient. The two films are vastly different in their subject matter and ideas, but my basic opinion of them are the same. An American in Paris clearly does many things very well, but the movie remains unimpressive to my self-centered, egotistical, and industry-killing Millennial eyeballs. It’s a fair movie, sure, but not one that I’d write home about. 0.

Bonus Points

None.

Final Score: 5/10

Oscar Facts

An American in Paris won the 24th Academy Award for Best Picture on March 20, 1952 at the RKO Pantages Theatre in Los Angeles. The award was presented by Jesse L. Laske and accepted by producer Arthur Freed. In total, An American in Paris received eight nominations, winning six awards, tied for the most of the evening. The film was only the second color film to win Best Picture after Gone with the Wind and the first film to win with no acting nominations since Grand Hotel.

George Stevens won Best Director, Humphrey Bogart won Best Actor, Vivian Leigh won Best Actress, Karl Malden won Best Supporting Actor, and Kim Hunter won Best Supporting Actress. Three of the four acting wins belonged to A Streetcar Named Desire, which was three of the four wins for the film. The event was hosted by Danny Kaye.

1 Comment