For the century following the American Civil War, the civil rights struggle, the fight for equal rights and fair treatment of African Americans, pockmarked the various events in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The struggle for equal rights came to a head from about 1954 until the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

The battleground for the struggle was in the American south, where prejudice and segregation reigned. Peaceful (led by Martin Luther King, Jr.) and even some violent demonstrations captured news headlines around the country and the world as the public turned their collective attention to various sit-ins, lynchings, marches, and riots. I would argue that even today, the country still grapples with racial issues and inequalities.

While civil rights fights are an unfortunate problem, unfortunately, they aren’t new, either. We’ve dealt with them for centuries and may be dealing with the far longer. Regardless, it’s our duties as Americans as we try to move into a “post-racial” world that we certainly study up on our history of civil rights struggles and brutal attempts to stamp them down. Only then can we truly move on. Of course, those who do not know the past are destined to repeat it.

That’s where this week’s movie, In the Heat of the Night, the 1967 Best Picture winner directed by Norman Jewison comes in. I’ll admit, I didn’t have high expectations for this movie. As I wrote in The French Connection, Hollywood at this time was making a transition from the white-washed and sanitized films of the 1950s and 1960s into movies that reflected a darker, more chaotic world in the last 40 years of the 20th century. The problem was that I felt like the movement began in the early 1970s with The French Connection, and then The Godfather and The Godfather: Part II. I was somewhat wrong.

In the Heat of the Night features the story of Virgil Tibbs (Sidney Poitier), a black detective from Philadelphia, stranded in a fearful, hateful, and largely narrow-minded small town in Mississippi where he is lucky to escape with his life. What started out as a crime drama with an unusual (at the time) schtick, ended as a powerful film on the impact of civil rights struggles with an overarching moral of acceptance and tolerance of our fellow humans. To say that the movie exceeded my expectations is an understatement.

Now for the rest of the movie.

Plot

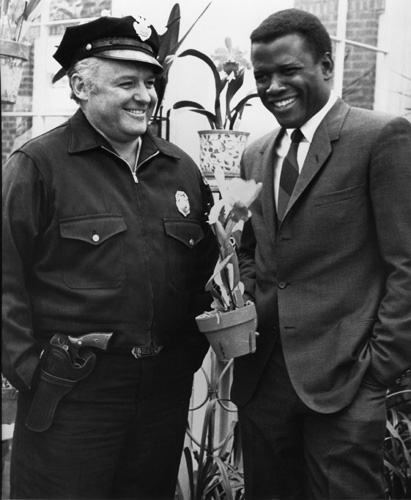

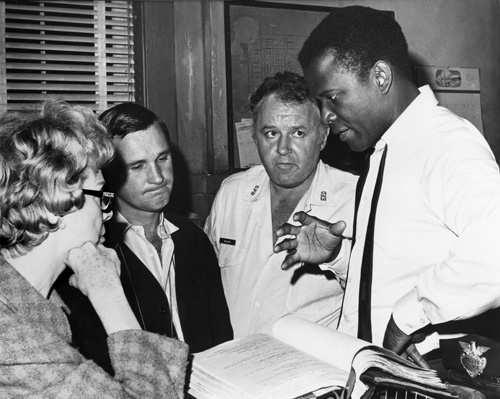

In 1966, wealthy industrialist Phillip Colbert moves to Sparta, Mississippi in the hopes of starting a factory there. When he is murdered late one night (the same night that Tibbs lands in Sparta, waiting for the train to Memphis), officer Sam Wood (Warren Oates), in a bid to find the killer, stumbles upon Tibbs and arrests him. Believing that Tibbs is the killer, Chief Gillespie (Rod Steiger) questions Tibbs aggressively. Tibbs lets it slip that he’s a homicide detective from Philadelphia. After reaching Tibbs’ boss to verify the story, Gillespie and Tibbs begin to work together in an oft-strained partnership to find the factory magnate’s killer.

Along the way, Chief Gillespie wrongly arrests two men and has to field pressure from local politicians and big fish to remove the black detective Tibbs from the case. Meanwhile, Tibbs examines the body and shows his incredible knowledge, prowess and stoicism in helping to gather clues and deal with unfriendly townsfolk.

From the start, the movie is definitely a crime drama. But it’s also a great crime drama by itself. It’s filled with terrific tension throughout and kept Laci and I on the edges of our seats. Full of twists and turns, the film has the makings of any great crime movie.

However, as I’ll explain soon, the movie has a deeper meaning. As the relationship between Gillespie and Tibbs gets more mature, their bond becomes stronger and they learn to not only respect each other, but protect each other. 1.

Writing

Originally, In the Heat of the Night is based on the 1965 novel of the same name by John Ball. The screenplay was adapted for the screen by Stirling Silliphant. The adaptation won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar.

Immediately, the dialogue is written in the traditional Mississippi prose, which is to say that it sounds like you’d think that it would. Full of incorrect grammar, the words lean on themselves. However, it soon becomes apparent that, like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the dialogue drives the story forward. Again, this is not an unusual phenomenon. The action, of which there is plenty, follows along justly. You’ve got to pay attention to this movie, otherwise the sophisticated Mississippian will pass you right by.

For a movie that takes place in the south, during the tumultuous civil rights movement, there are few cases of the use of the N-word. This only serves to add credibility to the story and the setting.

One final note, this movie has one of the best and most memorable lines in cinema history. Early on the in film, while Gillespie is antagonizing Tibbs, the latter blurts out with the classic line, “They call me Mister Tibbs!” The American Film Institute rates it as the 16th-best movie line in history. 1.

Sound

Composing the score for In the Heat of the Night was Quincy Jones. He was nominated for the Best Original Score Oscar, but for a different film.

The real champion of the sound for In the Heat of the Night is in everything outside of the score, particularly the upbeat jive of Ray Charles’ “In the Heat of the Night.” Outside of that piece, the sound department at Samuel Goldwyn Studio (won won the Oscar for Best Sound), used a number of funky and folksy contemporary songs to help set the mood. The music is definitely what townsfolk in Sparta, Mississippi would listen to. 1.

Set Design

In last week’s review of Moonlight, I talked about the “lived in” nature of the set. It was very natural. The same effect was in Kramer vs. Kramer. People actually lived in these sets and interacted there. It’s very authentic. In the Heat of the Night is the same way. The set is very intricate, down to the fly strips hanging from the ceiling.

There are also a ton of scenes shot outdoors. And this seems like a good time to mention Sparta, Mississippi, where the movie takes place. This version of Sparta is not to be confused with the actual Sparta, Mississippi. In response to Poitier’s concerns about being a black man in the south, the shooting location was moved to none other than Sparta, Illinois. This rural setting allows for an easy time conveying the small town vibe. Full of fields and plantations, In the Heat of the Night is as much a country movie as a crime one. 1.

Cinematography

Even though Haskell Wexler, the director of photography, was not nominated for Best Cinematography at the 40th Academy Awards, the movie still won the Oscar for Best Film Editing.

Right away, the defining style of In the Heat of the Night was the use of close-ups. By far the best shot for capturing emotions, the close-up was used quite liberally throughout the film. The shot captures everything from the sweat on Sam Wood’s brow, the flexing jaw muscles from Chief Gillespie’s feverish gum chewing, to Tibbs’ anger when he says, “They call me Mister Tibbs.” Each movie is a human story, and this one is particularly so because of the close-up.

While watching the film, I noticed (and loved) the fact that it looks so much like a color noir film. Noir, which originated decades before with classics like The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity, uses light and shadow and focused on style over practicality. The early noirs were black and white, but that’s not to say that the genre doesn’t transfer over to color. In fact, No Country for Old Men is a modern-day noir. In the Heat of the Night could be shot in black and white and it would look great. Stylistically, the lighting is superb.

One more note about lighting: it was softened to bring out features in Poitier’s face. Jewison made the decision to help capture his raw emotions in scenes. This film is one of the first to do that for African American actors. Most of them features hard white lighting which hid their features and emotions. 1.

Acting

There are really only two actors at play here: Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger.

Sidney Poitier plays Virgil Tibbs, a black homicide detective from Philadelphia. From the start, Tibbs is out of place in a town that doesn’t want him. He’s strong yet prickly at the beginning. However, he remains stoic in the face of adversity. He chooses to let his brain do the talking, rather than his fists, although he can defend himself. He matches everyone tit for tat and doesn’t care about not being welcomed in Sparta, determined, instead, to get to the bottom of the case with Chief Gillespie.

Most interestingly about Tibbs, and one that I think we can tend of overlook, is how he, a minority character, is portrayed as a smart human who is good at his job. He’s defiant, strong, and stoic, yes, but I think he shoulders the burdens and the expectations of a whole generation, an entire side in America, who were mistreated and underrepresented in both government and pop culture. He seems to be the African American character that the country needed at the time and Poitier plays it perfectly. It’s a true shame he wasn’t nominated for the Best Actor Oscar.

One interesting moment in the film, that was not in the book is while Tibbs and Gillespie are investigating the wealthy plantation owner Endicott, a vocal critic of Colbert’s factory. Endicott gets riled up and slaps Tibbs. Without wasting a second, Tibbs slaps him back. This particular kind of subversion of white authority was unheard of in 1967 with African American viewers cheering the scene and white ones booing it. Poitier advocated for Tibbs to slap Endicott, stating that it would the only natural reaction.

On the other side is Chief Gillespie, played by Rod Steiger, who won Best Actor for his role and we’ll see him again alongside Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront.

Chief Gillespie is a hard-nosed and veteran cop who has been around his one-horse town of Sparta plenty of times. He knows the ins and the outs, the politics and the attitudes of the townspeople. He’s also loyal to his men.

When he questions Tibbs at the beginning of the film, Gillespie comes across as the typical hyper-racist and incompetent police chief who has it out for those who do not share his skin color. And, to a point, that’s true. He’s a hard man to break from his prejudices, fighting with Tibbs throughout the entire movie.

He also has the curse to cut corners to appease the local bureaucrats and fat cats, but the gift of letting his curiosity get the better of him, following, as well as trusting, his hunches. He’s not a perfect cop and he gets in Tibbs’ way the whole time, but his arc is one of progressive tolerance and trust. His gut instincts that Tibbs is truly a special detective with an innate gift to solve crimes pays off for him in the end, but he must go through the meat grinder to get there. 1.

Directing

Taking the reins for this movie was Canadian director Norman Jewison. His efforts for In the Heat of the Night earned him a Best Director nomination.

Jewison’s first and foremost goal was to make a film about racism, or the fight against it. He reflected the strenuous civil rights struggles of the last 10 years and creates a brilliant microcosm of the American south played out in one little Mississippi town. The picture painted of a small southern town, wary of outsiders speaks about the whole of the south at the time. Sparta is bursting at the seams with racial tension. The same is true for the civil rights movement.

I’ve alluded to it above, but perhaps the most powerful message of the film is what happens when we can put our prejudices aside and just be good humans to each other. But it also shows the horrible and seedy side of intolerance. People resorting to violence to keep the status quo and threatening to kill another human being. The mob speaketh, and the mob speaketh as one in this case.

Yet, the more positive message wins out here, and it made me think. I’m pretty open minded, but I, too, have my prejudices and they show themselves without me even knowing it. The film forced me into a mode of deep introspection this week while I confronted my prejudices and my privileged life. For the last two weeks, we’ve jumped deep into race issues in this country and I think I’m the better for it. The messages preached by Norman Jewison in 1967 are every bit as relevant as today. If you don’t believe me, just think about all the political ads we’ve seen, having just come through election season. Us versus them and white versus black are two horrible and damaging fear campaigns that turn us against one another. Jewison shows us that great things can be accomplished when trying to change the status quo and when we put our prejudices aside. 1.

Bonus Points

I’m going to give a point to each acting and directing.

Final Score: 9/10

Oscar Facts

In the Heat of the Night won the 40th Academy Award for Best Picture on April 10, 1968 at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. It beat out Bonnie and Clyde, Doctor Dolittle, The Graduate, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (which also stars Poitier) for the award. The statuette was presented by Julie Andrews and accepted by Walter Mirisch, producer. In the Heat of the Night won five Oscars, the most of the evening, and earned seven nominations. Bonnie and Clyde and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner both earned 10 nominations.

Other notable winners that night included Mike Nichols winning Best Director for The Graduate, Katharine Hepburn winning Best Actress for Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, George Kennedy winning Best Supporting Actor for Cool Hand Luke, and Estelle Parsons winning Best Supporting Actress for Bonnie and Clyde. With Nichols win for The Graduate, the film is the only picture in history to win the Oscar for Best Director and nothing else. The show was hosted by Bob Hope.

Next Week

Gentlemen’s Agreement is next week’s film, followed by On the Waterfront, The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia, The Great Ziegfeld, Rain Man, and Cavalcade.

Very insightful review Keltin, I haven’t seen this movie but enjoyed your review!

LikeLike

Loved your disintegration of this piece of art! As a media student, I really enjoyed your insight! Keep up the good work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike